We see a deer, stalking in a field, on the way there. She has a torso of pure white, head a splotch of brown, and a baby following her snowy tail. She’s stark against the hush of the hill shadows, a ghost roaming her oat grass mountain grave. I think of the young deer colony in the park next to the fire station; I once counted 23 of them, just staring at me from the soccer field. Little horns were just starting to peek out of their tawny heads. The white deer is solitary— just her and her kid. Where are you off to? I think.

A blanket of clouds looks down on my car as it crunches down the gravel road. There’s a grey tint that transforms the little town into hues of muted sienna, taupe, and olive. We get out of my car, shivering as the wet grass rustles the hem of our skirts.

“If only it wasn’t so overcast. I wish it were sunset.”

“But imagine if it was,” I say, a visage of sun-spiked trees playing out before my eyes.

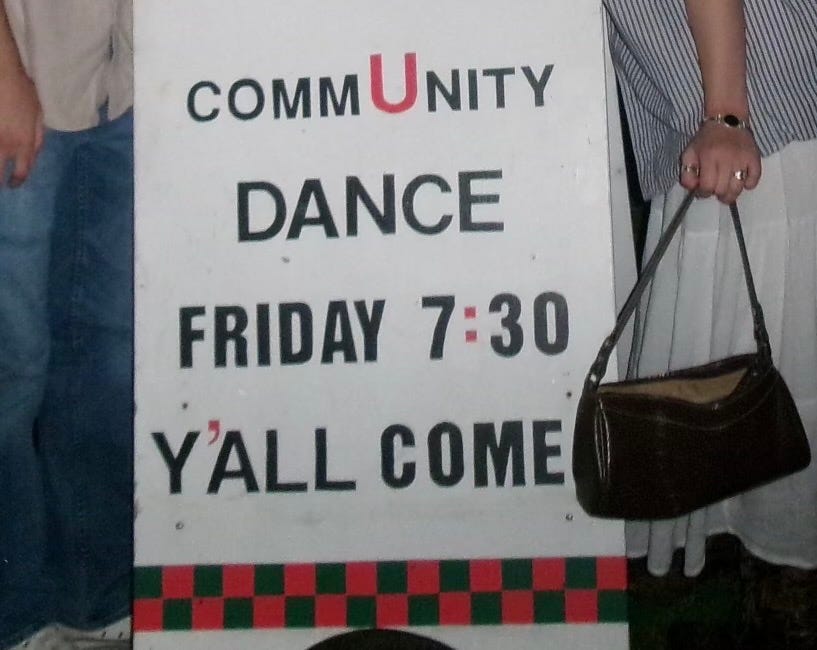

Friday. 7:30. Y’all come! croons a big sign planted in the lawn. Another sign simply reads LOVE, each letter a different color. The Mercantile is a creaky building, two floors, with a porch out front. A copy of The Pearl by John Steinback greets me from its rocking chair home next to the front screen door. I always believed that a good porch is not complete without a rocker. Wicker, just the right amount of pillows. I can hear banjo and laughter through the walls. Three flannelled men sit on the porch, puffing smoke into a smorgasbord of cards, lighters, and brown beer bottles. One of them has a silver tooth.

I consider asking for a cig, sweetly, and then am grounded by the fact that my tonsils are swollen to the size of grapes. Just that morning, I had woken up gasping for breath, body coated in a slime of sweat, from the steroids. The nurse had instructed me to get on my elbows, saying, This is going to hurt, and then shoved that needle into my ass like she had something to prove.

Thankfully, someone would have to kiss me to get what I have. Mononucleosis. That’s not happening anytime soon, I thought. Isn’t life surprising?

Simply put, my body craved to dance, and so it pushed me along that gravel road. I wanted to feel tethered to something— the warmth of a room, the knowing bow of a partner, the tip of a hat. If I didn’t know the moves, I could learn them. The connection craving inhabits me like the incessant hunger of a stray cat. I seek to replicate a portrait of intimacy of no other; this is the act of a square dance.

The closest metaphor I can think of is a first kiss. Putting your whole trust into those in your square, the caller, and the band plucking the tempo. You must listen to the call and replicate it. One second you are the crow in the cage, and then you’re sowing the clover. You will giggle and blush when you make the wrong moves. An older woman with wise eyes will give you an aware smile and it will feel like she knows all of your secrets, pinky promises, and midnight drunk confessions. You will watch a baby lope around on the dancing chest of a woman with a magnolia in her hair, and wonder if that child will grow up to remember the rhythm of a fiddle in her veins. Or if she’ll just have shaken baby syndrome. Only time will tell.

We walk in, put our 5 dollar donation for the caller in a giant pickled okra jar, grab a red birch or sarsaparilla beer, and climb up the stairs, passing the potluck and entering the 4x4 dance floor. Genuine Southern Squares! the poster had said. And here they are. We dance for some time, and then my body begins to give out, so I sit down in one of the chairs on the edges of the room.

And there he is. My devil.

I catch eyes with a man who looks exactly like him; his hair is in brown spirals and collects at the nape of his neck. A pit of fear forms in my stomach— small, like a cherry with arsenic in the middle. The floor is fire. The gates are open. I check for the black star on his right forearm, the one I watched bleed plasma as the tattoo artist stenciled it in. I note that there isn’t a mustache. He has one now, remember? You saw it on the bus. It stared at you from two seats away as your body froze. A bus has never felt smaller, more confining. He’s hot, I think, and I’m so disgusted with myself that I almost choke something up. I watch him dosey-do into the final notes of the mandolin, and then he leaves the room.

I imagine my spleen rupturing on the square floor. The doctor told me to stay away from contact sports (is square dancing considered a ‘contact sport’?) or that could happen. Dying at the Mercantile Community Square Dance. Internal bleeding from a misplaced elbow while doing the Texas Star. When I breathe, I feel the pressure flooding into my abdomen, cutting against my lungs. It would be so easy, I think.

I saw the Devil at the Mercantile Community Square Dance. Excuse my mono, and please believe me. That was all I wanted to hear. A boy looked me in the eyes a week ago and told me I believe you. I sobbed my mascara onto his shirt. Despite the extended metaphor, this essay is about intimacy, both wanted and unwanted. What does that mean to you? Have you ever seen the Devil? Where do you find your religion?

I slink outside the Mercantile, and I feel drunk with dance and high with the horror of seeing the Devil. One of the boys we danced with told us that he took a tab before this, and asked my friend if her polished nails grew like that, all blue and spotted like robin’s eggs. I am more crossed than he could ever imagine, my body pink and feverish as I sway to the clink of the moths from the porch lights, shoving their wings against the glass.

“I started plucking again,” one of the girls I danced with, Madeline, grins. She tells me her instagram handle and I pretend to write it down on my palm.

“You play banjo?” I am thoroughly impressed by anyone who can.

“My mom and hers passed it down.”

She tells me about how she’s an artist and likes to contra dance, too. She is not put off by my short bursts of questions. We realize that she went to the same highschool of my friend. It’s like that in our little Appalachia town; everyone knows eachothers’ brother or sister or cousin. I am not from here, but I find it comforting. I was born here, though, so I’d like to think that a part of me is linked back to the mountains that shrouded my cries.

I seek a story outside of my own, and hers brings me back to reality. Thank you, Madeline. I’ll see you at the next dance. After this one, I’ll drink Mellow Yellow tea in the shower and think of you as my lungs rattle.

I go back in and dance like my life depends on it. Looking back on it, maybe it did. I get so feverish that I have to throw my flannel onto a knob that is so smothered with coats that I think it could fall off any second. And there I am— a woman who has found her religion again, written in the margins between how do you do and fine, thank you. My brow wet with babtismal sweat, I am reminded that my God takes the shape of the kind woman playing the mandolin. The latch of one warm hand to another. The laughing crinkle in a friend’s eye. The queer couple embracing in the corner. The warm night air.